A Study in Basque Popular Stone Art

The Story

In 1940, fleeing the annexation and the Wehrmacht draft, a number of young Alsatians escape towards the South of France. Amongst them, the 20-year old Maurice Schmidt soon find himself without money or food on the platform of the Hossegor railway station near the Spanish border. There he meets by chance the mother of a family of 6 children that was caring for refugees; she adds him as child number 7 and hides him.

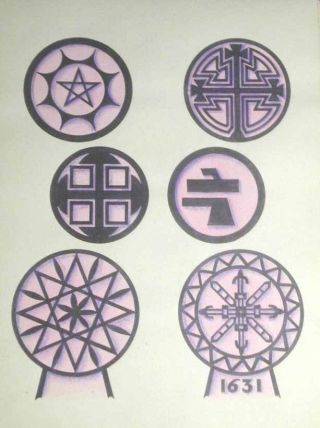

During that year, Maurice fell in love both with the Basque country and Mayi Lissarrague, his future wife of Basque origin. As they do not have much to do, they roam together the Basque villages on bicycles. Maurice is fascinated by the then almost unknown Basque stone popular art and especially by the large stone discs ['Discoïdales' in French] used as markers ['Stèles' in French] in graveyards, family compounds or throughout the countryside: see the drawing on the right. Most of these markers had been carved in the 17th century i.e. from 1650 to 1700.

Maurice, whose passion is architecture, started to draw the disks. Soon, he will go with Mayi from one village to the other reproducing with black ink ['encre de chine'] on his sketch pads a lot of these markers. What intrigued Maurice the most was that he realized that these markers are the expression of a truly popular art, made by untrained craftsmen tuned to the simple life of the village. To decrypt their messages, he also started to catalogue the drawings elements found in these markers, trying to find an alphabet that would open the meanings of each stone.

After the occupation of the 'free zone' of France in 1942, Maurice stopped drawing; by then, his work was about 95% complete. Again, he went into hiding, joining the resistance in the mountains in 1943. Maurice's Basque work from 1941 to 1943 is hereafter referred to as 'the work' or as 'Maurice's work'.

Maurice's work, 1946 to 1996: fifty years of sleep.

After the war, Maurice[1] recovered his 'basque work' in 1946 from a cache, and his work was left untouched until 1996. By then, most of the stone art described in Maurice's work had disappeared. Some discs were used as garden table, wall ornaments or paving stones for private driveways; others were just broken into pieces by hooligans. In the early 1990, scholars started to look again at the discs, that are the only expression of a 'Basque Stone Art'. The scholars lamented about the destruction of the objects; but soon, the word spread out about a trove of high-quality drawings made circa 1942 by an Alsatian refugee named Maurice Schmidt.

Since 1996 a few people have been able to consult Maurice's work stored at Mayi's apartment in Paris. Recently, Maurice's work got very high mark from Professor Duvert, Bordeaux University; Pr. Duvert will publish a 4 pages commentary in December 2003: [excerpt] "this work is an essential document about peasant art".

Maurice's Work

The result of all this roaming, drawing, thinking and classifying is a set of 11 books ['cahiers' in French] titled 'Tombes Discoidales, Steles & Croix - Libourg, Navarre & Soule-'.

Maurice's Work includes nine books of drawings and two books of notes: see picture on the right. In total, the work counts 632 pages.

Examples of the drawings

All photos, documents and text of this page: Copyright © Schmidt 2003 All Rights Reserved/ tous droits réservés.

[1] After the war, Maurice staid in the French army. In 1954-1955, he was one of the negotiators for the peace treaty with the North Vietnamese. He worked a lot on the nascent French-German civil and military partnership, earning -as a French Officer- the highest German military medal. With the rank of Général, he took an early retirement, then led the reconstruction of the Invalides in Paris, as well as the Château de Vincennes. He passed away in 1997.